| |||||

| LYLA BAVADAM

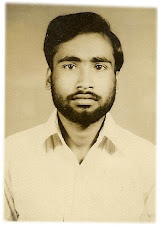

WHEN Vice-President M. Hamid Ansari released Asghar Ali Engineer's autobiography, A Living Faith, he described the author as a modern-day Spinoza. Comparisons of the two thinkers march side by side. Both are radical and free thinkers, grounded in moral philosophy and steeped in democratic political thought. Like the 17th century Dutch philosopher, Engineer has offered rational critiques of formalised religion. Asked about his work, Engineer said,"People have asked me why I wrote this autobiography. My only answer is that I felt like sharing my experiences, and I wanted to reach out to people who matter and who are concerned. I have three aims in life – peace and communal harmony, social reform, and gender justice. "Sixty-three years after Independence we are still lagging far behind in all these. Our society suffers from exploitation in the name of religion. Religion is supposed to make you humane and compassionate, but people kill in the name of religion. I discovered they kill because of vested economic interests, political interests. It is a clash of interests that causes violence – not a clash of religions as is commonly believed. I have given an account of all this in my book." Born in 1939, Engineer graduated in civil engineering and worked for 20 years as a sanitation engineer in the Bombay Municipal Corporation before he retired prematurely to work for the Bohra reform movement. He has authored more than 50 books and innumerable articles. He is the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies, the head of the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, and the founding chairman of the Asian Muslim Action Network. He is also one of the founders of the People's Union for Civil Liberties. He was awarded the Communal Harmony Award in 1997 and the Right Livelihood Award (widely known as the 'Alternative Nobel Prize') in 2004. For the past three decades, Engineer has been fighting for reforms in his Bohra community and has had to pay a heavy price for it: he was excommunicated and he faced physical assaults. He believes that "to be a truly religious person one has to have four qualities. A quest for truth. Humility. Compassion. Being anti-establishment. The reforms I am fighting for in the Bohra community… I am up against a very powerful establishment. I have met five Prime Ministers to try and get them to intercede in what is happening among Bohras, but they all told me they were helpless." His understanding of Islam is deep and uncomplicated and at the same time unsparing. Yet, as the historian Mushirul Hasan, who wrote the Foreword for A Living Faith, said, "… he argued for reforms and innovations within the inherited traditions." Reform movement There is a wonderful innocence in Engineer. A complete believer and follower of his faith, he cannot fathom the authoritarian manner in which it is being applied. The majority of the community acquiesce to the absolute authority of the high priest, Syedna Burhanuddin, who controls the community with an iron hand. A handful of people do not. Engineer is one of them. His earliest experience with the diktats of the high priest was when he, as a young boy, was told that he would have to perform sajda (prostrate oneself) before the Syedna. He refused, saying it was un-Islamic since sajda is performed only before Allah. A marshal who noticed his refusal caught him by the neck, called him a shaitan (devil) and forced him to prostrate himself. The haplessness of his father in that situation must have served to keep the memory alive in the young Engineer. Many years later, when he wrote an article in support of Bohras in Udaipur who had challenged the Syedna, Engineer again felt the heat of the powerful priests. A group of angry Bohras surrounded the building of The Times of India in which the article appeared and threatened to burn it down if an apology was not printed. The newspaper banned future articles by Engineer, but that was not the end of his tribulations. His relatives and friends pressured him to apologise. In all clarity and innocence of belief, he writes, "I maintained that there was no question of apologising as I had not done anything wrong. I was against exploitation in the name of religion and not against religion per se. I was fighting against exploitation and restrictions on freedom of expression which is both my Islamic as well as constitutional right." But his relatives would not accept these arguments. "They prefer to buy their way to peace rather than fight for any principle, much less the principle of freedom," he writes. Finally he was presented with an ultimatum. "They said that if I wanted to maintain any relationship with them I would have to withdraw myself from the reform movement or they would never see my face again. I said I would prefer their absence than give up my fight for freedom. No one from my family ever met me thereafter." That last line, so powerful in its reality, is written with a moving simplicity, and is typical of Engineer, who has never dramatised his life even though there is enough material in it for a thriller. His mother, torn between her loyalty to the Syedna and her love for her son, chose the former but was still taunted by the community. Engineer writes of how she would sometimes come to his office and "weep before my colleagues…". When he and other reformists launched the democratically elected Central Board of the Dawoodi Bohra Community at an all-world reformist Bohra Conference in 1977, stories of oppression began to flow from among the one lakh delegates who attended. Engineer writes: "In one case in Udaipur, a father who was with the reformists died of acid burns and his son who was Shabab (an orthodox Bohra organisation) was forced to marry on the day his father's funeral procession was held. He was even asked to curse him." Unlike the rest of his community, many of whom acknowledge that greed is the driving force behind the tyranny, Engineer has refused to tolerate it. This is actually a refusal to be cynical, and to that extent he is truly a revolutionary, albeit a non-violent one.  Asghar Ali Engineer. For the past three decades, he has been fighting for reforms in his Bohra community and has had to pay a heavy price for it. He was excommunicated and also assaulted. Interestingly, Engineer is himself the son of a priest and was brought up with strict and deep religious training. This makes his arguments all the more strong as he is completely capable of a serious debate on religious knowledge. The establishment recognised this and saw him as enemy number one. His work in garnering support for the reform movement was tediously slow. The Bohra establishment wielded power by fear, and this prevented many from supporting Engineer. But small things such as the gathering of 64 signatures from the staff of the Aligarh Muslim University, assistance from Jayprakash Narayan, and the overwhelming support of almost all sections of the media furthered the cause of reform. But regardless of all this and despite the fact that Engineer made the movement an international one, he feels sad that the community is still in the grip of the high priest. Social and religious reformer, linguist, intellectual, writer – there is no all-encompassing label that describes the author. He is as much a student of Marx as he is of Farman Fatehpuri, the Urdu scholar who authored seminal works on the poets Mirza Ghalib and Muhammad Iqbal. Marx guided him to take an objective view of religion while he still remained grounded in the essential teachings of Islam. In his book he writes, "Although I remained a believer, I too was converted to Marxism. In my opinion it is not necessary to be an atheist to be a Marxist." Taking his cue from Christian liberation theology which originated in South America, Engineer learnt to take the best of all knowledge from diverse streams. This thirst for combining faith and reason – what perhaps can be called pure knowledge – is something of a trademark. Being open to all influences is particularly valuable in the current age where exists, as Kumar Ketkar, editor of Divya Marathi, says, a "dangerous trend of middle class and intellectual conviction that justifies communalism". Engineer's endeavours for communal harmony began in the post-Emergency days when the Janata Party was in power. Communal violence broke out in Aligarh, Varanasi and Jamshedpur. When Indira Gandhi returned to power, the dangerous trend continued, with the politicising of communal tensions. After a number of riots in Biharsharif in the early 1980s, Engineer went to investigate them. He found that the "RSS machinery was well oiled in the area and it spread rumours in villages which were instrumental in spreading the violence". Then came the Shah Bano case, the conversion of Dalits to Islam in Meenakshipuram (Tamil Nadu), riots in Meerut and Bhagalpur, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid. Throughout, Engineer attempted to gather information, prepare reports and keep passions low on both sides, but the voice of moderation was not heard. He says he had the distinct feeling that Indian secularism was being shredded. His involvement with secularism and anti-communal work is a natural corollary of his reformist work. The obvious common bond is that he is committed to building an inclusive society, one in which humanity overrides all else. If there is any criticism of the book, it is that it does not reflect adequately the dangers, the violence, the struggles and the tireless striving that have been a part of Engineer's life. It is not that he avoids these aspects of his life – he cannot because they are what have made the man – but he describes them with a blandness that is almost disappointing to readers, especially those who have followed his work via newspaper reports. For instance, take the case of the very first attack on his life; an incident that most other people would describe in minute detail is dismissed in a couple of lines by Engineer. It happened in Calcutta [now Kolkata] in 1977 when Engineer had hired the Muslim Press Club for a press conference to further the reformist cause. The Syedna had heard about the press conference and paid a large amount of money to the club to cancel the reservation. Of what must have been a tension-charged atmosphere, Engineer writes, "I found the premises locked and waited with a journalist friend for someone to come and open it. Suddenly some people began gathering around us. I became suspicious but stood there. Soon a large number of Bohras and some goondas collected there and attacked me. I could not run. But my journalist friend knew some young people from the area and summoned them to help me. They lifted me bodily and fighting their way out, took me to a nearby building which was a safe place. I escaped death very narrowly." A striking quality about Engineer is his rationality and his calm approach to whatever comes his way. This equanimity is what comes across as one turns the pages of the book. On reflection, even though there seems to be a disconnect with the turbulence of his life and his manner of relating it, it is actually a fitting style for Engineer to tell his own story. "It is difficult to write an autobiography because in our society to come out with the truth is a very challenging thing to do," said Engineer. "I have tried to be honest and truthful… as much as a human person can be." There is no doubt that the book is a perceptive commentary on society written with unassuming scholarliness. It is an accurate representation of the author and his life and hence a true autobiography.

|

Current Real News

7 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment